Illegal Dogs in the UK (Dangerous Dogs Act 1991, Section 1)

Back in 1991, the UK government brought in legislation aimed at tackling the issue of dangerous dogs after a spate of high-profile dog attacks.

In the period 1990-1991, there had been 11 serious dog attacks, seven of which were on children. The resultant media-driven public outcry led to the then Home Secretary, Kenneth Baker pledging to “rid the country of the menace of these fighting dogs” and rushing legislation through parliament with minimal debate in only six weeks.

While many criticised it as knee-jerk, flawed legislation, Baker argued that the Act was necessary to protect the public from “specific inherently dangerous dogs” – and there is no doubt that there was an issue with social unrest resulting from recession, which gave rise to a fashion for irresponsibly-kept (and often criminally used) ‘macho breeds’, especially within inner cities.

While only four of these attacks had involved Pit Bull Terriers, this is the breed that the media christened “devil dogs” and that bore the brunt of much of the resultant legislation.

Part of this legislation, Sct 1 of the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991, is known as breed specific legislation (BSL), which deems certain breeds illegal. This breed specific approach has been consistently questioned over the years and is often seen as one of the most controversial laws ever passed - and indeed in all the time this legislation has been in place, dog attacks have not decreased.

Despite that, in 2023 the Government announced that a new breed/type would be added to the list of prohibited dogs – the XL Bully.

So, what are the five prohibited breeds of dog in the UK and what does this mean for owners?

The Dangerous Dog Act 1991

The Dangerous Dog Act 1991 is legislation created by the government on the 25th of July 1991 as a response to growing national concern over dog attacks and irresponsible ownership, with the aim of protecting the public. There are two main parts to it.

Section 3 relates to any dog of any breed that behaves in a way considered to be dangerous and states that it is a criminal offence for an owner or a person in charge of a dog to allow the dog to be ‘dangerously out of control’.

Section 1 however relates purely to certain breeds of dog, and classes them as being illegal to own in the UK. This has nothing to do with any incidents or behaviour from the dog/s concerned.

In respect of Sct 1, the original legislation ordered the mandatory destruction of all dogs on the banned breed list. There were limited exemptions under certain conditions possible but only for dogs born before 30th November 1991. This included them passing a court assessment that they would not pose a risk to the public, being neutered, microchipped, insured, and being kept on a lead and muzzled at all times in public. The idea was that the breeds would disappear in the UK as these exempted dogs naturally died out.

While there were irresponsible and even criminal owners of Pit Bull Terriers, this legislation led to the seizing and death of hundreds of much-loved family dogs who had never behaved in a dangerous way or ever put a paw wrong.

One of the many flaws in the legislation was that the wording of the law said that it was illegal to own a dog “of the type known as the American Pit Bull Terrier” as the APBT had never been a recognised breed in the UK, so many court cases came down to months of experts arguing as to whether or not a dog was or wasn’t an illegal dog based entirely on the way they looked and a set of measurements. The law had a reverse burden of proof so unlike most UK laws where you are innocent until proven guilty, if an owner had their dog seized under Sct 1 DDA 1991, it was up to them to prove their dog wasn’t an APBT.

Following years of campaigning, the Dangerous Dogs Act 1997 amended this mandatory destruction order so that a dog found guilty of looking a certain way could be exempted if, having gone through the court system, they passed a behavioural assessment and agreed to adhere to strict rules.

These include that the dog must be neutered, microchipped (and with up-to-date information), have third party insurance, and be muzzled and on a lead at all times in a public place. The owner had to be deemed to be a right and proper person to look after the dog, to make sure the dog was kept secured within their property, and to comply with the regulations. The dog must be kept at the owner’s home and could not be bred from, rehomed, sold, or have ownership transferred.

Why are some breeds banned in the UK?

The spate of attacks that led to the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991 were largely thought to be carried out by American Pit Bull Terriers (although only four of the 11 attacks that led to the DDA were indeed carried out by Pit Bulls) – a strong powerful breed, bred for fighting and capable of causing serious injury and even death. Kept irresponsibly or criminally, these dogs made for a very effective weapon in the wrong hands and the Act was in part brought in to tackle what was seen to be a growing problem in inner cities.

While the Act was being drafted, other fighting breeds were looked at to see whether it would be prudent to include those in case they became a problem or even took over from the APBT.

What dogs are illegal in the UK?

There are currently five illegal breeds in the UK. The original breeds included in the DDA 1991 are: the type known as the American Pit Bull Terrier, the Japanese Tosa, the Dogo Argentino and the Fila Brasileiro – with the XL Bully being added to the list in 2024.

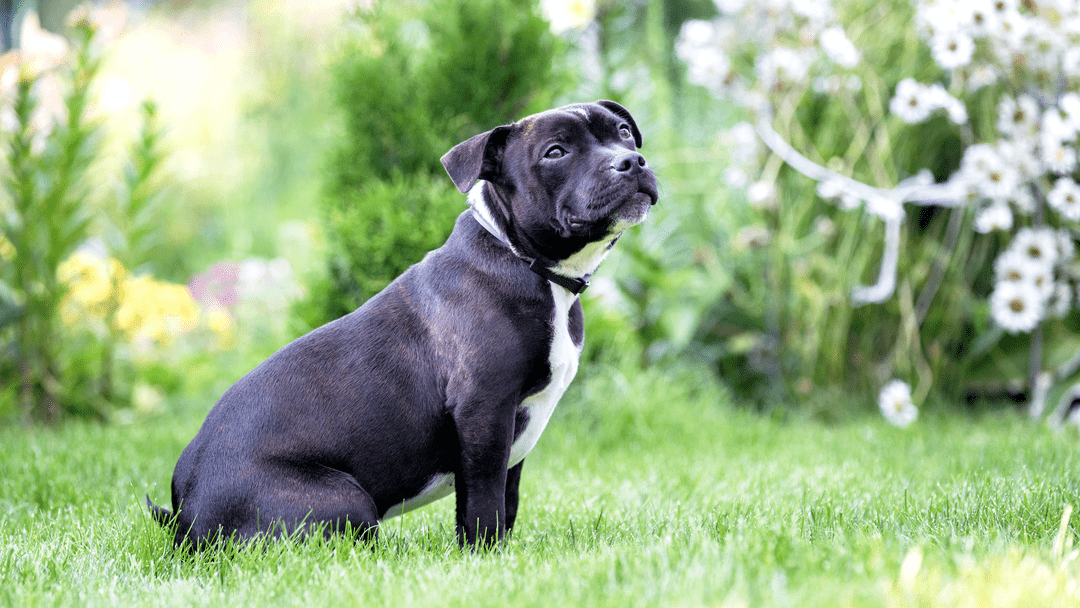

The American Pit Bull Terrier

The origins of the American Pit Bull Terrier can be traced back to the bull breeds of Victorian England where blood sports such as bear and bull baiting were popular as a source of entertainment, even amongst the nobility. In 1835 however, the British Parliament outlawed all baiting activities and so those who made money – or gambled – on the outcome of such barbarism had to find another outlet. Dog on dog fights were cheaper, legal and needed little space. Fighting dogs were developed and perfected to create fast, agile animals that were tenacious, strong, perseverative – and while friendly to humans, would fight to the death.

Some of these fighting dogs were exported to the United States where they were further developed to be bigger and stronger with the aim of creating the ultimate fighting machine – the American Pit Bull Terrier.

Interestingly however the strength, agility, drive and intelligence of the breed coupled with their loyalty, meant that with responsible ownership and training, they were able to turn their paws to whatever job their owner wanted them to do – and so many found work as service dogs, search and rescue dogs, detection dogs are well as competition dogs and family pets.

Japanese Tosa

The Japanese Tosa was and still is fighting dog in Japan (although now rare) and compared to the American Pit Bull Terrier, is a giant of a dog. Weighing up to 90kg and looking like a cross between a Mastiff and a Great Dane, this is a dog who was prepared to fight to the death, and do so in complete silence - fearlessly and relentlessly attacking their opponent without any hesitation

Their reputation as the ultimate fighting dog led to the breed being included in the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991 – despite there never being more than a handful (if that) outside of Japan. The Japanese Tosa is also included in breed specific legislation in several other countries.

Dogo Argentino

The Dogo Argentino was bred in Argentina not for fighting but for big-game hunting, with its prey being largely wild boar, puma and jaguar. The breed was created by two teenage brothers and became their lives’ work, using a wide range of breeds including the thankfully long-extinct Cordoba Dog (a fearsome fighting breed known for its extreme aggression) along with Pointer, Boxer, Bull Terrier, Bulldog, Dogue de Bordeaux, Pyrenean Mountain Dog and the Spanish Mastiff. This created a pure white dog that looked like a large Pit Bull Terrier that quickly found employment as a hunting dog but also as a guard dog, police/military dog and even a guide dog, thanks to their extreme bravery and protective instincts. These instincts however make it a fearless guard, willing to fight any intruder without mercy – even to the death. These behavioural traits, together with its large, muscular, powerful build capable of inflicting serious injury, led to the Dogo Argentino being added to the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991.

Fila Brasileiro

The Fila Brasileiro, which is commonly known as the Brazilian Mastiff, is a large dog bred in Brazil. This is a breed created from the local mastiffs brought to the New World by the Conquistadors, crossed with Bloodhounds and other bulldogs. This created a fearless hunting dog with enormous stamina and strength – blending size, scenting ability and tenacity in one huge and formidable package.

The breed was used originally as a hunter’s aid – employed to track, attack, and then grab and hold the prey until the hunter arrived – and the word ‘Fila’ comes from a Portuguese word meaning ‘to hold’. The breed is known to be suspicious of strangers – indeed in countries where they are shown, judges are told never to touch them and judge from a distance – although they are said to love their own family!

These strong hunting and fearless protection instincts, coupled with their size and strength (and hatred of strangers) have resulted in them being banned in many countries.

XL Bully

The latest addition to the list of breeds prohibited under Sct 1 of the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991 is the XL Bully – the only ‘breed’ currently to be added after the original legislation. As with the American Pit Bull Terrier in the DDA, the XL Bully is a type and not a breed, and so identification comes down to physical conformation and a list of measurements created by the Government as part of the legislation.

The XL Bully was added to the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991 effective in England and Wales from 1st February 2024, and as with the original legislation, there was an exemption for existing dogs as long as owners applied for a Certificate of Exemption by January 31st 2024 and were bound by the conditions of exemption (neutering, up to date microchip details, insured, on lead and muzzled in public place etc).

Scotland and Northern Ireland have followed England and Wales by also banning XL Bully type dogs.

Now that the deadline for exemption has passed, it is a criminal offence to own or possess and dog of XL Bully type in the same way as the four originally banned breeds.

What if I own a banned breed in the UK?

Owning an unregistered dog of any of the five breeds/types prohibited under the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991 is a criminal offence in the UK.

There is no way to voluntarily register any of these dogs now, and the only way a dog can be exempted is under a Court Order after the dog has been seized by the police.

Possible exemption would be at the discretion of the Court, would be subject to all the conditions of ownership of a registered dog (see below), and only after the Court has satisfied themselves that the dog wouldn’t constitute a danger to the public. If an owner can’t satisfy the Court of this, or if the Court feels that the owners is not a fit and proper person to own an exempted dog, then the dog will be euthanised.

Conditions of owning a registered dog

- The registered keeper must be an individual and be over 16 years of age

- The dog must be neutered

- The dog must be kept on a lead (which must be held securely by someone over 16 years of age) and muzzled at all times in a public place (including in a car)

- The dog must be microchipped and all details kept up to date

- Owners must keep the local authority up to date with where they live at all times.

- The registered keeper must have third party insurance in their name in the event the dog injures someone

- The dog must remain in the possession of the registered keeper (except for a possible 30 days in any 12-month period) and must be kept in secure conditions so they can’t escape

- Keepership of an exempted dog can’t change, and Defra must be told if the dog dies or is exported.

- No person shall breed from the dog, sell or exchange the dog, allow the dog to stray or abandon the dog.

If any of these conditions are breached it is a criminal offence, and the dog is no long exempt - and there is a presumption that the dog will be euthanised.

So far over 57,000 XL Bullies have been registered with Defra in the UK. Many of these are very possibly not XL Bully types but owners were scared that if they didn’t register their mixed bull breed looking dog in the very short time given to do this, they would have to have their dog put to sleep after the exemption period ended.

Defra have said that there will be ways to withdraw a certificate of exemption for people who feel that their registered dog is not an XL Bully but details of this haven’t been made public yet although the Government website says that more information about how to do this will be available “soon”.

The Government advice to owners who think they have a dog that falls under the legislation regarding XL Bully types is to contact the local police force but understandably people are either unaware that their friendly family dog would be classed as an XL Bully, or are too scared to come forward as they are frightened of losing their dog. Others, as with APBT, have no intention of being responsible owners or complying with this (or indeed any) law!

The subjects of the Dangerous Dog Act Sct 1 and the topic of what makes dogs ‘dangerous’ have been and continue to be heavily debated.

It has long been suggested that irresponsible breeders and owners are to blame for the behaviour and reputation of some breeds, while others argue that generations of irresponsible and intentional breeding for behaviours such as aggression result in certain breeds being more dangerous than others.

Others will say that how dogs are kept, exercised, trained, socialised and managed is the defining factor in the safety or otherwise of some of our larger, stronger and more powerful, breeds, and that given knowledgeable owners who are able to keep dogs in a suitable environment and give them an appropriate outlet for their hardwired behaviours, any breed can be kept safely.

Critics of breed specific legislation (and this includes the RSPCA and many of the dog welfare organisations) argue that banning dogs for their looks and not their behaviour fails to address the causes of aggression or protect the public, as any dog can bite and cause injury. They argue that ‘deed not breed’ ie legislation that focuses on the behaviour of both a dog and owner, along with better education, enforcement and early intervention, is the only way to tackle the very real issue of dog attacks.

Whatever the reality – and it is likely a combination of all – breed specific legislation has failed to reduce the number of dog attacks and bites in the UK.

These differences in opinion will continue to be discussed, although it seems unlikely that breed specific legislation will be repealed anytime soon.